Global warming caused by environmental degradation is creating havoc in every country with erratic weather patterns becoming the norm rather than an exception. Even though the most advanced, developing, and poor countries have pledged to address this humongous criterion in the making more holistically, the action on the ground simply resonates with mere lip services lacking concrete measures that could help sustain the environment to be reasonably under control. While we were growing up, the seasonal occurrences were almost precise save for some minor alterations here and there.

PC: manishsiq

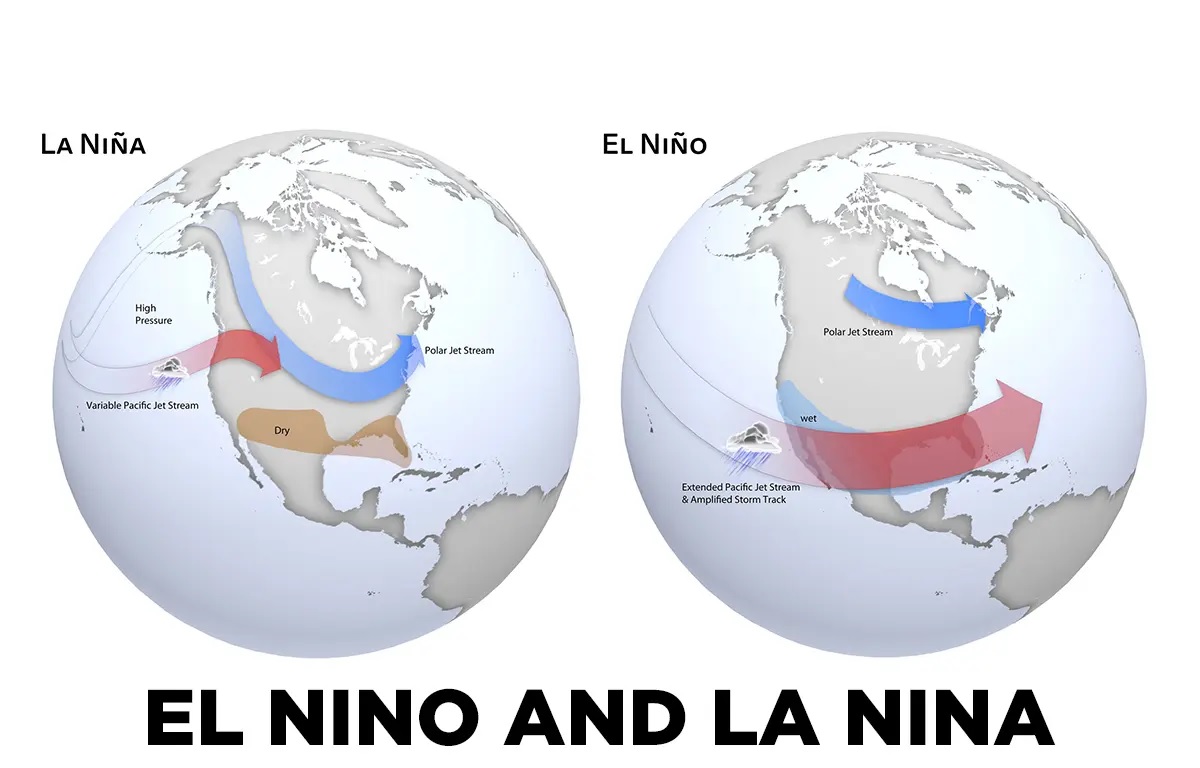

Generally speaking, the weather patterns were predictable, throwing no surprises whatsoever. However, the weather patterns have altered over the years. The El Nino and La Nina have become synonymous with the weather patterns around the world causing governments to prepare for the unpredictability factor along the way. As regards India, we are still largely an Agri-based economy dependent on the monsoon for its irrigational needs. Now, two aspects of the southwest monsoon – June to September – stand out as observed recently. After four years, we had a monsoon that was slightly below normal – cumulative rainfall of 82 cm was 94.4% of the long period average.

Within that headline number, the sharp monthly swings in rainfall stood out. If it was 113% of LPA in July and September, it was just 64% in August. An effect of climate change is an increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall events. Note that the IPCC had estimated that extreme daily precipitation events would intensify by 7% for every 1 degree Celsius of global warming. It calls for a shift in the most important aspect of India’s agricultural policy. The cornerstone of it is the procurement system for rice and wheat, which secures supply for about 800 million people the PDS targets.

A combination of both minimum support price and a subsequent guarantee of procurement is the foundation of regular supply. For farmers, it cuts down operational risks. Consequently, the political economy of procurement has led states such as Telangana, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh to make a concerted effort in recent years to procure rice. Worryingly, a fallout of this trend is that the central plank of India’s agricultural policy is out of sync with emerging climate risks. Remember, rice is a water guzzling crop that’s increasingly catered by tubewells. Not only does it add to water stress, but it also holds back electricity reforms as free power to farms lowers cultivation costs.

PC: Hiren Kumar Bose

Of course, the way to break out of this logjam is to incentivize farmers to shift from paddy and wheat to millets. Among cereals, millets not only need less water but also are more climate resilient. India is the world’s largest producer of millets and GOI encourages its cultivation. However, the area under millet cultivation has not seen an increase though. GOI must tweak the policy that prioritises millet procurement by backing along MSP lines. Further, India’s climate adaptation strategy needs to lower the economic risks of millet cultivation for farmers as well. Yes, this is easily done but requires a policy push from GOI.